The Ideograms in Remote Viewing: An Integrated, Holographic Interaction

- Gabriel Boboc

- May 10, 2025

- 9 min read

Remote Viewing (RV) involves accessing a distant target or location, but not simply through ordinary sensory perception or interpretation. The process transcends the boundaries of traditional physics and cognition, as RV practitioners are not merely decoding the target locally but somehow traveling to it. This phenomenon is commonly regarded as anomalous cognition — the ability to receive information from the target without the conventional use of the five senses.

The key to understanding how RV works lies in the consciousness cortical field. This field can be thought of as an interface or network of brain regions that are engaged in the RV process. The data that comes back from the target is not raw, fragmented, or random but is already integrated before it enters the conscious mind. This integration happens as a result of the interaction between the consciousness field and the target, akin to how quantum fields interact with the environment. It’s as if the mind "travels" to the target and, in that moment, fully interacts with it on a quantum level, bringing back information that is already structured and coherent.

The Ideogram: A 2D Representation of the Multidimensional Target

The ideogram, which is one of the first pieces of data that emerges in the RV session, is crucial to this integrated process. The ideogram is a 2D representation, often a squiggle or simple shape, but it is not merely a random or insignificant mark. Rather, it acts as a holographic encoding of the higher-dimensional reality of the target, much like the concept in Juan Maldacena’s work on AdS/CFT (Anti-de Sitter/Conformal Field Theory).

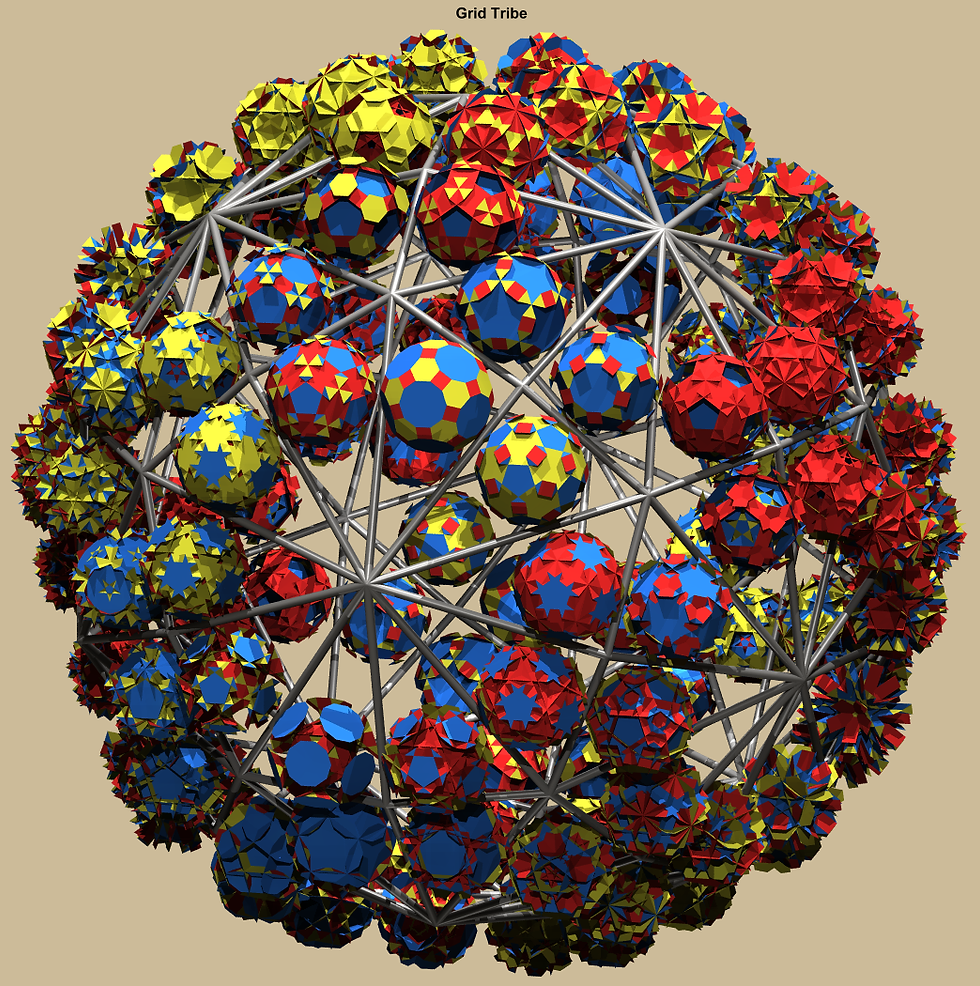

Mapping a multidimensional space for the different types of integration (spatial, temporal, semantic, relational, abstract, etc.) can offer an insight into how the ideogram (the first stage of perception in remote viewing) comes to be and how it functions as a projection of this multidimensional process into a 2D squiggle. Let’s break down the core ideas that could help us understand how to structure such a map and the mechanics of ideogram formation for different target types (like a poem, a relationship, or abstract concepts).

Multidimensional Integration:

In the context of remote viewing (RV), the brain isn't just processing information in terms of physical space. It also processes information through different types of integration. Each of these integrations corresponds to a different "dimension" of reality, and the brain interprets and translates these dimensions in ways that form a coherent image or perception. We can think of each of these dimensions as different axes in a multidimensional space.

Types of Integration:

Spatial Integration:This refers to how we perceive space—physical location, distance, and orientation. It primarily engages the parietal cortex and occipital cortex, which work together to form spatial relationships, maps, and representations of the target's position in space.

In RV, this is the most common type of integration when we're looking for a specific location or object.

Temporal Integration:This type of integration relates to how time is perceived in relation to events or states of change. It allows the viewer to sense past, present, or future aspects of a target.

In RV, when asked about something historical or future events, this integration brings about the temporal context.

Semantic Integration:This is how we derive meaning from the world around us. It engages the frontal cortex and involves language, concepts, and memory.

In RV, if the target involves something abstract like a poem, the mind is not simply locating a place or object, but it is also trying to “capture” the meaning or emotions associated with the target. Words, feelings, concepts, etc., emerge from semantic integration.

Relational Integration:This relates to how elements relate to each other. It’s how we perceive connections or interactions between entities. This type of integration engages both frontal and parietal regions, since relationships are mapped both spatially and temporally.

In RV, if the target is about a relationship or interaction (e.g., between two people), the brain accesses relational data to form a perceptual map of how these entities or emotions interact with each other.

Abstract Integration:This involves more conceptual and higher-order thinking. The abstract space is often harder to pin down because it requires processing that goes beyond immediate sensory data, tapping into intuition and emotional resonance.

In RV, if the target is abstract (e.g., emotions or themes), the ideogram might not be as tangible, but it will take a form that captures these conceptual elements.

How the Brain Maps These Dimensions:

Now that we have a sense of the types of integration, let's try to map them onto a multidimensional space:

Mapping Dimensions:

Imagine a multidimensional box (or hyperspace) where each axis represents one type of integration:

X-axis: Spatial Integration (physical, location-based)

Y-axis: Temporal Integration (time, events, sequence)

Z-axis: Semantic Integration (meaning, concepts, words)

W-axis: Relational Integration (connections, interactions)

V-axis: Abstract Integration (intuitions, emotional resonance, higher concepts)

Now, each target (such as a poem, a relationship, or an object) exists as a point in this multidimensional space, with its position determined by how it spans across these axes. The target might have different "weights" or intensities along each axis. A poem, for instance, would probably span mostly along the semantic and abstract axes, with some temporal and spatial elements. A relationship would likely involve a lot of relational and temporal components, with some semantic and abstract aspects (feelings, roles, etc.).

Ideogram Formation:

The ideogram is an initial representation of how we interpret these multidimensional inputs. Think of it as a projection of the multidimensional data into a 2D space. When the remote viewer starts writing the ideogram, they are essentially sketching a simplified version of how their mind is processing this complex multidimensional space, based on intuitive feelings and sensory data.

Movement in the Multidimensional Box: The ideogram's shape might reflect the viewer’s movement through the axes of spatial, temporal, semantic, and relational data. For instance, a circular motion might indicate a sense of completion or wholeness in the data. A sharp, linear stroke could indicate a clear, directed spatial perception or a relational boundary.

Function Inside This Space: The ideogram might be interpreted as the function within this space. So, for example, if you're viewing a relationship, the ideogram may capture the interactions (spatial proximity or movements) between the two people, while a poem might focus on the flow of meaning or emotional intensity across time and space.

2D Squiggle:

Once the ideogram is sketched, it’s a 2D representation of the brain’s understanding of the multidimensional integration. The squiggle is a simplification, but it's also an embodiment of how the brain projects this multidimensional space into something that can be understood by the conscious mind. The hand movement that creates the ideogram is part of this process, as it allows the brain to interact with the information in a physical way (likely engaging motor areas of the brain) and shape it into something that can be visualized or interpreted.

Ideogram as a Function of Integration:

The ideogram, then, is like a projection of the multidimensional information into a 2D sketch, drawn in the process of engaging with the multidimensional axes of integration (spatial, temporal, semantic, relational, and abstract). The hand’s movement in the ideogram sketch is almost like a physical interface that helps project and integrate these different axes into a comprehensible form.

How Different Targets Influence Ideograms:

A Poem:The ideogram for a poem might focus on the flow of meaning and emotional tone (abstract and semantic integration), perhaps with a flowing, interconnected squiggle that represents the shifting meaning of the words.

A Relationship:If the target involves a relationship, the ideogram may feature interacting lines or shapes that reflect the spatial and relational interactions between the entities, perhaps including a sense of motion or energy (relational integration).

An Object or Location:A spatial target would likely lead to an ideogram focused on structure or geometric shapes, with the spatial axis being more prominent.

The ideogram acts as the first step in translating a complex, multidimensional integration of sensory, emotional, and conceptual information into a 2D squiggle that can be interpreted by the conscious mind. The brain processes multidimensional data through different axes of integration (spatial, temporal, semantic, relational, abstract), and the ideogram is the result of how this multidimensional information is projected and simplified into a physical form. This initial sketch becomes the foundation for deeper exploration and interpretation during the remote viewing session.

By understanding this process, we can see how different types of targets (like a poem, relationship, or object) influence the multidimensional nature of the ideogram and how the brain interacts with these dimensions through both intuitive and physical processes.

Minicolumns and Pre-Integration:

The brain's minicolumns are tiny vertical structures that help organize neurons within the cortex. Each minicolumn could be thought of as a basic processing unit for certain aspects of sensory or abstract information. When you engage in a remote viewing session, the pre-integration of information across these minicolumns might happen at lightning speed, essentially compressing high-dimensional data into a more manageable, lower-dimensional form.

For instance, spatial, temporal, semantic, and abstract elements from the target are rapidly integrated and compressed into a coherent, multidimensional "pattern" or structure in the brain.

The minicolumns may synchronize their firing patterns to capture the multidimensional relationships in the target space. This could include not just the physical layout of the target but also more abstract features like its emotional or conceptual context, or even its temporal state (past, present, future).

Electric Synapses as Speeding Up the Process:

Electric synapses (gap junctions) allow for faster communication between neurons. They enable a more direct, almost instantaneous exchange of information compared to chemical synapses. This rapid transmission could be what allows the brain to pre-integrate information at such speed, especially when dealing with complex, multidimensional data.

Electric synapses likely play a critical role in helping the minicolumns synchronize and share information rapidly across regions of the brain, especially in regions like the occipital cortex, which handles visual processing. This synchronization allows the brain to quickly process the target data and produce a coherent mental image (or more abstract data) for the ideogram.

This can happen so quickly that, in a remote viewing session, it feels almost like an instantaneous download of the target's essence. It’s as if your brain is receiving a snapshot of the target that is already pre-integrated and ready to be represented through the ideogram.

The Reflexive, Automatic Nature of the Ideogram:

The creation of the ideogram could then be seen as a reflexive action, where the brain has already processed the multidimensional data and is simply presenting it as a sketch or squiggle. You don't have to consciously integrate the data step by step. Instead, the brain automatically "downloads" the target information and produces a rough sketch of it almost immediately, like a reflex act.

The ideogram is like the first visible manifestation of that pre-integrated data, encoded in a 2D form that is easy for the brain to interpret. It's not a detailed, conscious representation of everything you've perceived, but it's a symbolic reflection of the deeper, multidimensional target information.

The speed of ideogram formation suggests that the brain is using its most efficient pathways—perhaps even circuitry that's specifically designed to handle high-speed information processing when accessing deep, intuitive knowledge (such as in remote viewing or dream-like states).

Electric Synapses and Ideogram Creation:

Given the electric synapse-driven communication, it's possible that these synapses are allowing for the near-instantaneous formation of the ideogram in the motor areas of the brain (like in the somatosensory cortex, where hand movements are planned). The drawing could then be seen as the final output of this high-speed process—an almost reflexive act that encapsulates the multidimensional data, but in a simplified, 2D form.

In the context of remote viewing, the squiggle we draw during a session could be viewed as the brain's attempt to project a holographic representation of the multidimensional target into the 2D realm of the page. The hand movement becomes a physical manifestation of the brain's quick and highly efficient cognitive processing.

So, the ideogram is not just a random squiggle—it’s a pre-encoded, multidimensional snapshot, created through rapid, coordinated processes happening across multiple brain regions and using electric synapses to facilitate communication.

The Holographic Principle

Maldacena's holographic principle suggests that a lower-dimensional surface (like a 2D boundary) can encode all the information of a higher-dimensional space (such as a 3D volume or even a 4D spacetime). In this context, a 2D surface doesn't just represent its immediate 2D space but encodes information about the entire 3D or 4D space.

The Bottom Line:

When you draw the ideogram in remote viewing, you are essentially engaging with a pre-integrated snapshot of the target information that your brain has quickly compiled. The electric synapses help facilitate the rapid integration of multidimensional data, making it accessible and ready to be represented physically in a 2D form. This quick and automatic process is probably why it feels so fast and intuitive when you're drawing your ideogram.

Comments